Inside This Issue

- “You can’t shoot another bullet until you’ve reloaded your gun” : Coaches’ perceptions, practices, and experiences of deloading in strength and physique sports

- Intramuscular Hyaluronic Acid Expression Following Repetitive Power Training Induced Nonfunctional Overreaching

Study: “You can’t shoot another bullet until you’ve reloaded your gun” : Coaches’ perceptions, practices, and experiences of deloading in strength and physique sports

How long, how often, and how aggressively should you deload? How do deloads differ between different strength and physique sports?

Introduction

Deloading is a common practice amongst coaches when prescribing training. However, the frequency, amount, and type of deload often vary significantly depending on coach experience and preference. Deload can be planned within a fixed timeline such as a 3:1 or 4:1 paradigm which means three or four weeks of loading followed by a recovery week. In contrast, some plans use autoregulation that does not set when a deload should occur but looks at signs and symptoms of pushing too hard and too long from athlete responses.

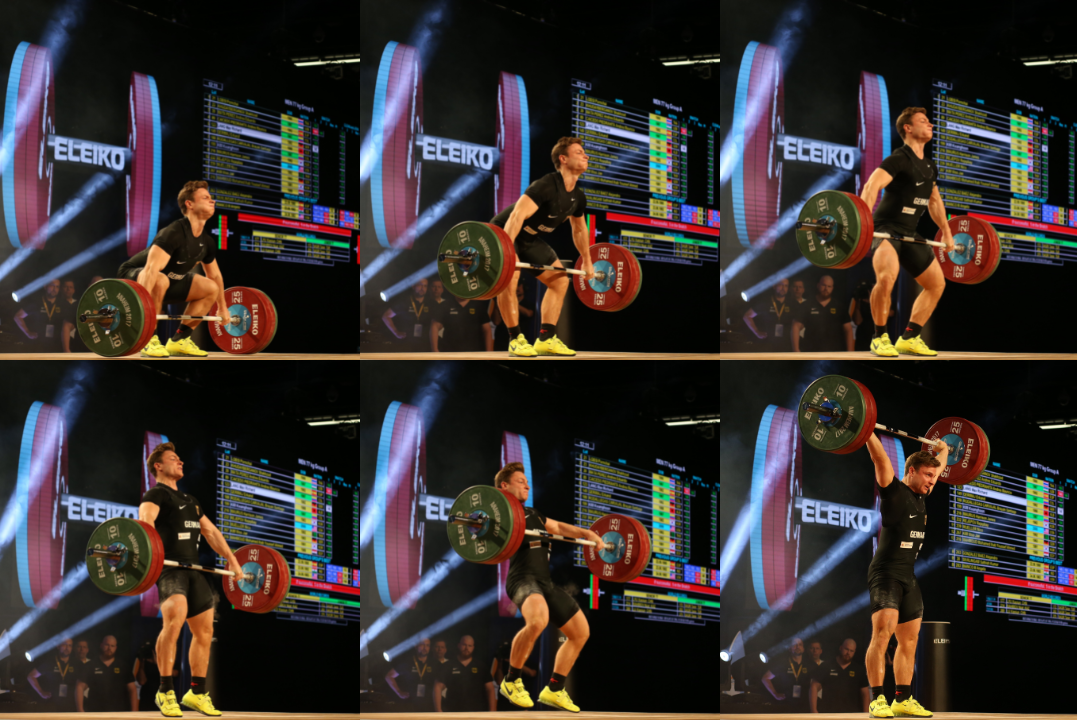

Further convoluting this topic are the disparate sports that coaches may encounter. The training means of a bodybuilder, powerlifter, and weightlifter are all different and thus may require different deloading protocols. While deloading is commonplace there is a stunning lack of research on this topic. Therefore, this study investigated coaches' actual practices of deloading and attempted to better understand why, when, and how the use them in the training of strength sport and physique athletes.

Purpose

1. Look at current practices in deloading

2. Providing framework on how to study deloading in research

3. To compare and contrast deloading and tapering

Methods

This study employed a qualitative descriptive design that consisted of semi-structured interviews with coaches. Due to this methodology they recruited subjects on a first come first serve basis and were able to locate and interview 3 weightlifting coaches, 12 powerlifting coaches, and 10bodybuilding coaches for a total of 25 participants. All coaches were of national to international rank mainly from North America but also had some world representation from the UK, Australia, and New Zealand.

The interview questions are open access and can be found at this link for the supplementary material. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sports-and-active-living/articles/10.3389/fspor.2022.1073223/full#supplementary-material

In studies such as this, they look through interviews that are transcribed and look for themes and groups of responses. They took these broad response groupings and placed them into “definitions”, “rationale”, and“application”. This leads to several subcategories which you can find in table 2 of the paper listed below (1).

Results

Definitions

Training demand outlined how coaches classify the deload in which they stated its easy training that was different from normal training.Next, they compared this to a taper. The main outcome – deload is embedded in the training plan whereas the taper is done before the competition. Finally, they were asked if these terms are interchangeable with each other and the answer was no.

Rationale

Most responses in this category were around the purpose of a deload and the major themes were fatigue management and recovery. They spoke about how using this period in a training plan can lead to restoration and recovery. Finally, this section covered progression. Coaches highlighted that in most cases planned rest and deloading is necessary for long term adaptation and progression.

Application

The last section was the longest and delved into the understanding of how coaches are applying deloading in practice. The main points are this:

Volume - decreased from normal training but with no consensus on the total amount but ranged from 25-50% pre-deload volume

Intensity of effort - There was less consensus here with some coaches opting for reductions in volume as the primary factor and others with reductions in intensity.

Frequency - Maintain frequency was most common

Duration - the typical response was one week

Exercise variation - Varied responses on this category with no consensus

Individualization - coaches agreed here that adjusting the deload based on the athlete was important.

How often (Periodicity )- ranged from 3-12 weeks.

Proactive vs reactive - two camps here both had reasons for why.

Discussion

The key take homes concepts from this article were: 1)coaches consider deloading separate from tapering and peaking and that it should not be confused, 2) the main reason for using a deload was fatigue management with a focus on recovery and adaptation, 3) a wide variety of applications are found in the field likely due to the categories of coaches interviewed for this study.

When examining the literature there is a surprising lack of research on deloading considering it is so pervasive across multiple sports.When we restrict ourselves to strength and physique sports it's typical for coaches to have planned or reactive deloads every 4-8 weeks depending on the system with physique athletes deloading at longer intervals (8-12 weeks).Intuitively, this makes sense based on the demands of the training protocol.Weightlifters and powerlifters generally train with higher intensities more often in their training than a physique athlete so this may necessitate the use of deloads more frequently. Additionally, though volumes of training during physique training are typically larger than powerlifting and weightlifting training the focus is on muscle stimulation and quality controlled repetitions which are likely to cause less total muscle damage and stress on the system.Furthermore, they can use a wide variety of repetition ranges to achieve their ends whereas strength sport athletes use a more narrow band of training repetitions and volumes that change the nature of the stress.

Under application, there was a wide range of answers on certain categories such as volume and intensity. This makes sense when considering the different training systems and methods that coaches employ.Volume was reduced on average 25-50% from pretraining values which is similar to the tapering and peaking literature which is around 40-60%. Intensity wasless clear with some coaches placing this first on the list for constructing a deload and others focusing on volume. In any case, it seems that a reduction in intensity, either RPE/RIR or absolute loading can be built into this phase. Themost typical duration seems to be one microcycle which fits well into a mesocycle format and allows the athlete to recover without losing much trainingtime. Finally, it appears that coaches are in two camps using autoregulation(unplanned) and planned deloads in training. Again, this is likely built upon the sport and coaching methods but none of the coaches interviewed stated thatthey did not include a deload in their plan.

PracticalApplications

Included below is the final table from the paper which details the recommendations.

References

1. Bell, L., Nolan, D., Immonen, V., Helms,E., Dallamore, J., Wolf, M., & Androulakis Korakakis, P. (2022). “You can't shoot another bullet until you've reloaded the gun”: Coaches' perceptions, practices and experiences of deloading in strength and physique sports. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 1073223.

Study: Intramuscular Hyaluronic Acid Expression Following Repetitive Power Training Induced Nonfunctional Overreaching

What happens in the muscle with overreaching? How much volume is too much volume for an overreach?

Introduction

During the training process, coaches often seek training methods that can provide a performance benefit to their athletes to outpace their opponents. Most, if not all coaches, employ a tapering and peaking phase which can provide a 0.5-5% increase in performance depending on the athlete's competitive level (1). Another tactic is the use of an overreaching phase which is a brief period of high-intensity and sometimes high-volume training that pushes past their current level of recoverability but if properly implemented upon recovery leads to a boost above baseline that could not be achieved by normal training means. If used in conjunction with a tapering and peaking period may lead to a podium finish versus a middle-of-the-pack result.

Within the overreaching literature, there are a few key terms to consider. First is functional overreaching, this term is described by a planned reduction in an athlete's preparedness which will recover and hopefully exceed baseline following the tapering and peaking phase. Next would be the non-functional overreach, which is a term for a condition in which the reduction in the athlete's preparedness was expected but did not return to baseline before the competition. This condition typically will reverse itself in weeks. Finally, you have overtraining syndrome. This term is for an unplanned reduction in performance as a result of too much volume or intensity or a combination of both. This syndrome is problematic in some cases when discovered could be the end of an athlete's career. If you can reverse overtraining syndrome, it’s on the timescale of months to years.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine non-functional overreaching which involves power training. To do this they measured muscle tissue and looked at a specific protein expressed following training.

Methods

From a previous investigation, they determined the athletes were overtrained and had blunted/stagnated power adaptations. All subjects had 2+ years of consistent training.

Methods

The subjects completed a one-repetition maximum (1RM) back squat, 1RM leg extension, and speed squats at 60% of the back squat max.

Training protocol

The nonfunctional overreaching group did 10 sets of 5 reps in the back squat at 60% of 1RM in the speed squat followed by 3x10 at 70% in the leg extensions twice a day. They completed a total of 15 sessions in 7.5 days. The control group did 5 sets of 5 reps at 60% for the speed squat and the same leg extension protocol. They completed only three training days.

Muscle biopsies

Muscle biopsies were obtained from the vastus lateralis muscle group pre and post-study and the key protein indicated above was obtained for analysis. Hyaluronic Acid (HA) the specific protein in this study is found in abundance within the extracellular matrix and I necessary for muscle function related to contraction.

Results

No effects were observed for the control group. In contrast, there was a 34.5% reduction in HA in the NFOR. While hinted at in this study this was part two of a larger investigation. In the other study included below, power was unaffected in the NFOR but was increased in the control group (4).This indicated a stagnation in performance which is expected in NFOR.

Discussion

The main outcome from this study was that in subjects forced into nonfunctional overreaching a key muscle protein related to muscle contraction was reduced by 34%. Additionally, power stagnated in the experimental group while power increased in the control group. While this is impractical for any athlete or person to undergo this protocol it does show that it is possible to overreach and potentially overtrain with resistance exercise.

Tied to results from the earlier publication, this study showed that following this protocol, androgen receptors and protein pathways were depressed, whereas glucocorticoid receptors (stress) were increased only in the NFOR group. This tied together with the depression in the muscle tissue from the current study demonstrated the negative effects of nonfunctional overreaching. While most coaches are not doing muscle biopsies following hard training this provides evidence that unplanned stressful training can have negative impacts on the muscle and this may manifest as decreases or stagnation in performance.

There are several considerations for this study. First, the two groups completed two very different protocols (15 sessions vs 3 sessions).It’s unknown how many sessions are needed to tip someone from overreaching to non-functional overreaching. Would seven sessions completed once a day instead of 15 done twice result in the same outcomes? It’s hard to say from this study.Next, they did the same training every single day. Weightlifters may snatch and clean and jerk each day in the same session during a tapering and peaking phase but typically training has multiple days with different exercises that may change the outcome for the athlete. Finally, we can imagine working with areal-life athlete and attempting to do something like this. They may start to question your methods after day two or three of doing a protocol like this and simply not come into the gym or force you to change the plan. Unlike Bulgaria where the government owns you or this experimental study, going this hard for along period is not feasible with the modern athlete in a free society.

Practical applications

Don’t do high volume twice-a-day training for seven days and expect performance to improve. What we can learn from this is that you can induce nonfunctional overreaching with athletes but it’s likely difficult to do and with sound training methods based on previous experience you can prevent this in athletes. Extrapolating out to weightlifters, double-day training is not a problem if volume and intensity are managed and during a time of trying to overreach an athlete this provides some data on how to approach that with an individual athlete.

References

1. Purdom, T. M.,Wayland, A., Nicoll, J. X., Ludwar, B., Fry, A., Shanle, E., & Giles, J. (2021). Intramuscular hyaluronic acid expression following repetitive power training induced nonfunctional overreaching. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 46(12), 1563-1566.

2. Le Meur, Y.,Hausswirth, C., & Mujika, I. (2012). Tapering for competition: A review. Science & Sports, 27(2), 77-87.

3. Fry, A. C., & Kraemer, W. J. (1997). Resistance exercise overtraining and overreaching:neuroendocrine responses. Sports medicine, 23, 106-129.

4. Nicoll, J. X.,Fry, A. C., Mosier, E. M., Olsen, L. A., & Sontag, S. A. (2019). MAPK, androgen, and glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation following high-frequency resistance exercise non-functional overreaching. European journal of applied physiology, 119, 2237-225

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)