Everyone has had that “aha!” moment with their technique after doing a drill or variation of the snatch or clean and jerk and instantly felt their technique click. In this case, the puzzle piece was a movement that “taught” the athlete what they needed. I’ve had this happen with the no hook, no feet variations – as have most of my athletes. It’s akin to driving a particular route to and from work but one day finding another route with new scenery, coffee shops (a must), and less traffic. Okay, you’re probably sold at this point, but how do coaches and athletes reliably create that “aha!” moment? Or is it just up to luck… Well, I have good news for you, and it starts with one weird trick.

What’s a Technique Primer?

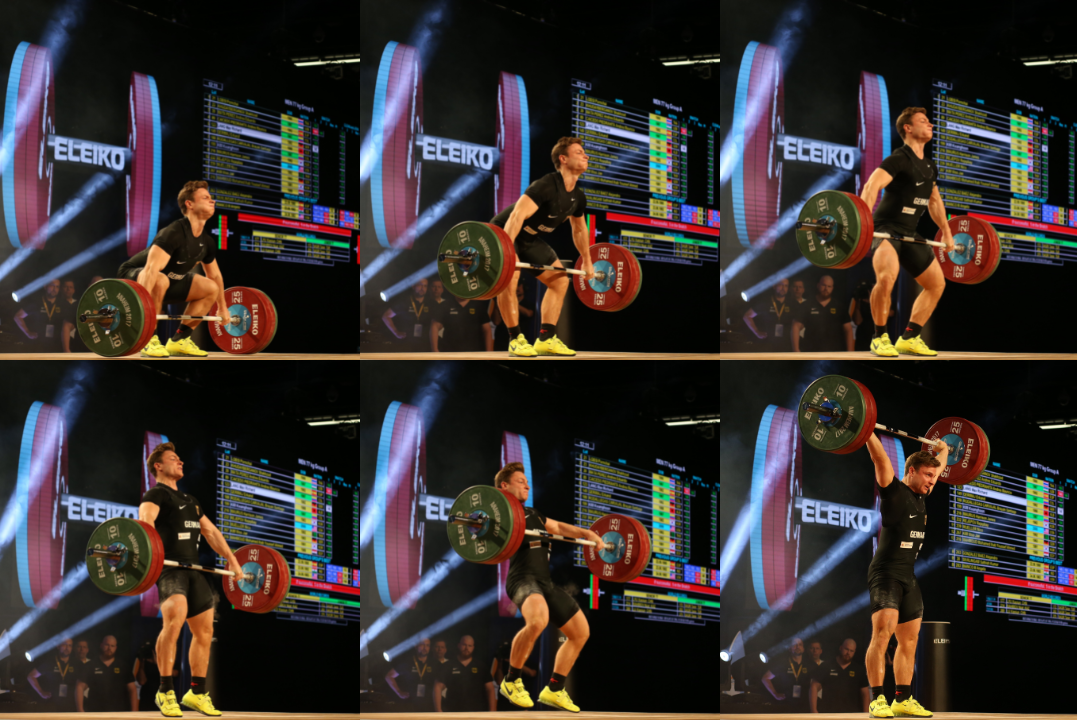

Before we dig into the application, let’s provide more context. Specifically, technique primers are drills or movements used early in a session before main exercises to reinforce positions or timing elements of that lift. They are like “bridges” between general prep and specific execution. This differs from a complex, a topic I’ve written about extensively here, in that the movement is performed in isolation, not as a string of lifts.

An example of a technique primer would be:

Movement 1 (Primer)

- No Feet, No Contact Power Snatch

- 3 sets, 5 reps at 50-60% of 1RM snatch

Movement 2 (Special Exercise)

- No Feet Snatch

- 5 sets, 3 reps at 70-75% of 1RM snatch

An example of a complex would be:

Complex (Special Exercise)

- No Feet Power Snatch + No Feet Snatch + Overhead Squat

- 4 sets, 1+1+1 at 65-70% of 1RM snatch

If you want a full-on deep dive into the topic, Max Aita and I have covered this extensively on episode 167 of the Philosophical Weightlifting podcast. The main idea of a primer is to support immediate changes in technique, which then potentiate the next exercise an athlete will perform, typically one with heavy weights, more specific to the classic lifts. Although accomplishing this end, primers are not warm-ups and are not always complete variations (think snatch balance). They’re targeted, often shortened movements that enhance technique and create a heightened awareness of what the athlete is doing. The benefits are gleaned from the low fatigue cost, efficient sequencing, and increase in attentional focus on important aspects of the movement.

Primers are Typically Low Fatigue

Simply put, fatigue is the “tax” on exercise – which is complex and far beyond the scope of this article. It is generated from training and augments performance in largely undesired ways (e.g., decrements in force production, both magnitude and rate). A few necessary things to know: fatigue accumulation is correlated with intensity (% of 1RM) when volume (sets, reps) is equated, exercise displacements (think: range of motion), and proximity to failure (e.g., when you’re closer to failure, you’ll generate more fatigue).

Escaping the nuance prison that is fatigue, we can more comfortably discuss how primers fit into this. Primers are typically low intensity (less than 60-70% of 1RM), meaning they are less likely to generate meaningful amounts of fatigue—this is the point. The work is intended to be high quality, focused, and supportive of the rest of the training session.

Example primers and their intensities:

Snatch

- Snatch Grip Press in Squat (20-45%)

- Power Position Power Snatch (50-65%)

- No Hook, No Feet Snatch (55-70%)

Clean

- Tall Clean (30-45%)

- Muscle Clean (40-55%)

- Hang Power Clean, Above Knee (60-70%)

Jerk

- Press in Split (30-40%)

- Close Grip Overhead Squat (40-60%)

- Power Jerk, Pause in Dip (50-65%)

Sessions are Sequenced Seamlessly

In weightlifting, powerlifting, strength and conditioning, and any performance-focused training session, there is an immense value placed on the structure of the training day – for more specific details on how to do this, read Hayden Pritchard’s fantastic article. The training day should maximize the return of the session, be it muscle growth, increased strength, improvements in power, or a combination of adaptations. This requires appropriate sequencing of movements to manage fatigue and potentiate the next movement or string of movements. Primers do this beautifully.

With lower loads, more movement constraints, and a focus on specific technical flaws, primers generate minimal fatigue, are typically faster, and prepare the athlete for the next higher-intensity exercise. This creates a session that looks like this:

Warm-up

- Dynamic movement (bar work, body weight squatting/hinging/lunging)

Primer

- Muscle Snatch w/o Contact (emphasis on a high pull with the arms/shoulders)

Special Exercise

- Classic Snatch

General Exercise

- Pause Back Squat

Accessory Work

- Snatch Grip Press

- Clean Grip Upright Row

- Hanging Knee Raises

Channeling an Athlete’s Focus

Recently, I had a conversation with an athlete about being able to switch on mentally. We all have the experience of lifting weights, a somewhat passive process of grabbing the bar and doing the exercise as needed to check a box. On the other hand, we have all had the experience of being so engaged with our lifting that it felt like all of our energy, effort, emotion, and ounce of concentration were poured into this singular moment. That’s the difference between exercising and high performance. Being engaged with training in a way that draws our concentration to the task at hand and maximizes the chance of tightening up a technical error or adding a few more kilos to the bar – this matters.

Primers are a means of bringing heightened awareness to technical inefficiencies – flaws in our sights for remediation. We can sequence the session to concentrate attention, dial in the focus, and increase the athlete’s engagement.

This is the Beginning

This article has laid the groundwork for understanding the importance of technique primers before the main work within a session. Including them brings benefits, including error remediation, enhanced focus, and more efficient workouts—all at a low fatigue cost (talk about a great return on investment). Future pieces in the series will include my favorite primers for each lift and how to sequence training over the medium and long term.

Now, you’re equipped with a better understanding of the training day, exercise sequence, and how this fits into the bigger picture of performance. You’re more than qualified to tell all of your friends about this one weird trick.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)