With the popularization of “research-backed” practice, there’s still a surprising number of coaches who use cookie cutter templates and adhere to a system-based approach when writing programs. System-based approaches are blueprint-style, mostly one-size-fits-all, approaches normally attributed to specific regions, clubs, or coaches (e.g., Russian, Bulgarian, Chinese, LSUS, Westside… you get the point). These approaches use a predetermined micro, meso, and macrocycle structure, which, while effective for some, ignore the importance of individualization.

Using this framework fails to take advantage of a scientifically founded and objectively analytical method of program design. As coaches in this great sport, collectively we should want to both create the best process for improving our own athletes, and the processes other coaches use to develop theirs. This means changing the sport, not just copying and pasting sets and reps.

Being Process Driven: Don’t just talk about it, be about it

Process-oriented program design is the antithesis of system-focused training plans. It singles in on the process of individualizing training, ultimately iterating to the point of optimality for a given athlete. This process will account for volumes, intensities, how frequently certain intensities are programmed, how each block feeds into the next, and eventually, exercise selection.

To build champions, you will need to master these concepts.

Volume: Rep Distribution Overview

In this context, volume will refer to the process of breaking bigger chunks of work, tracked by repetitions, into smaller and smaller units. This may seem daunting, and to some extent learning a new skill and putting it into practice when it matters always is, but it’s worth the pay off once it’s mastered.

Typically, a four-week training block should contain between 800-1200 repetitions. Assuming the plan will contain 800 repetitions in the mesocycle the repetitions can begin to be bucketed out into weekly and daily volume prescriptions. These repetitions can be categorized into low impact (60-70% intensity), moderate impact (70-85% intensity), and high impact. (intensities greater than 85%) This distinction is somewhat arbitrary, as are most ways of categorizing the world, but it provides us a less-wrong starting point and a place to refine our own system.

In weightlifting the primary goal of training is to increase weight on the bar and manage volume well enough to retain previous adaptations (e.g., increases in muscle mass and work capacity). This will require a masterful management of both intensity and volume, as they are somewhat inversely related (i.e., as one goes up, the other must typically adjust down).

Note: If you’re interested in learning more, read this article from Josh Gibson on the complex relationship between training volume and intensity.

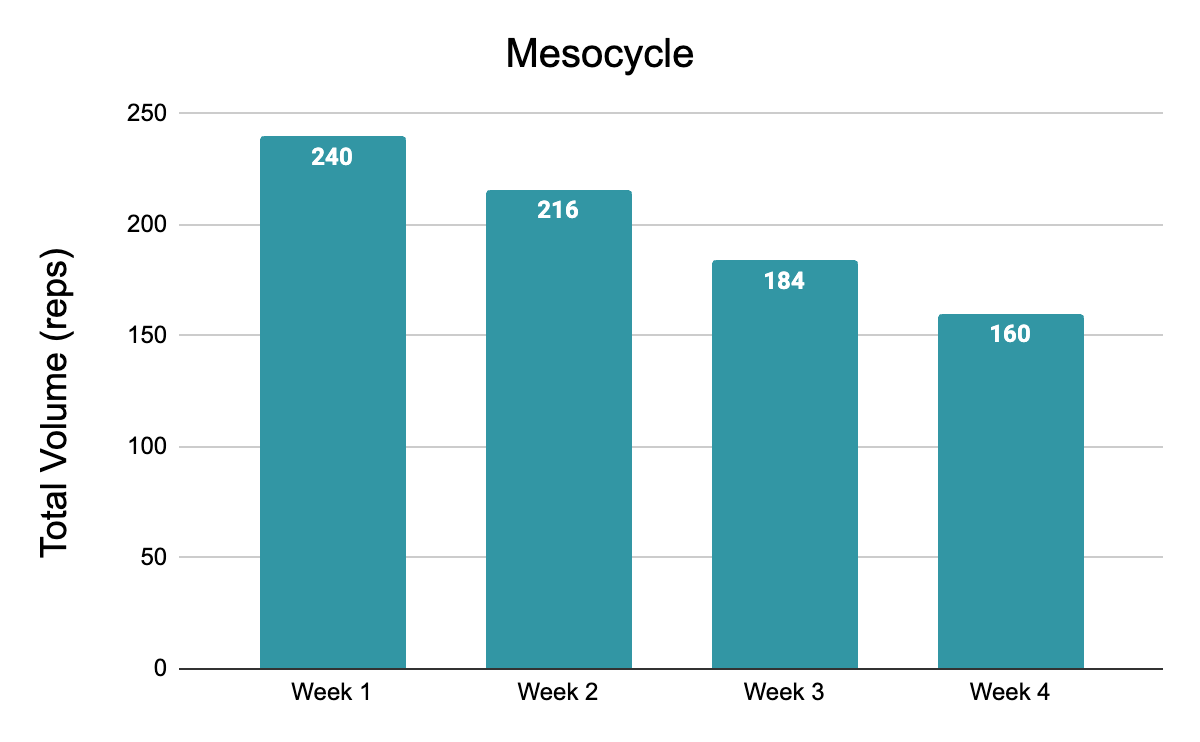

Visualizing the previous mesocycle recommendations, we have:

In this graph, you notice that as the weeks progress, there is a steady decrease in total reps. This works out to approximately 30% of the total volume during week one, 27% in week two, 23% in week three, and 20% allocated to week four. If you start from this point, it can be easier to break the training weeks into individual days, distributing the respective rep counts.

Volume: Writing a Training Day

Having laid out the number of reps within each week of a mesocycle, we can start populating workouts. A training week will generally have 3-5 workouts, with our example there is some flexibility depending on athlete preference and schedule constraints. For the higher volume weeks, more workouts would make each training day more manageable. As you get to weeks 3 and 4, reducing the number of training days by ~1 could be feasible and help more effectively manage fatigue during high intensity weeks or consolidate stress during deload.

The obvious place to start is week one, assuming for the sake of this example that the athlete will train five sessions a week. It would be easy to evenly distribute the reps across each workout, and while this may work for a short time, this doesn’t optimize for fatigue management and/or overload. It could be more beneficial to break the volume up in an undulating pattern, assigning large, small, and medium sessions throughout the week.

Visualizing microcycle recommendations, we have:

To create sustainable training, day one will be higher stress consisting of 30% of the weekly volume, followed by day two which is a smaller session consisting of 13% of the weekly volume. After a lower volume day, the reps can increase so day three will be another large session consisting of 27% of the weekly volume. Following three workouts, day four will be off, allowing for recovery before two medium sessions occupying days 5 and 6 – each 15% weekly volume.

Although more detailed, the extra time spent to work this out beforehand will allow for more effective training, more sustainable training, and overall better results. Unlike a system, this process is not rigid, as all volumes are subject to adjustment by the coach based on the current and future needs of the athlete.

Intensity and Exercise Selection: Getting Specific

When volumes are laid out it is easier to construct a training day with exercises and intensities to push up results. For week one, day one there are 72 repetitions to build the session, broken up amongst a somewhat arbitrary number of exercises (1-2 competitive or special exercises, 1-2 general exercises, and 2-4 accessory exercises). For the larger movements, repetitions will be distributed as needed, with general blocks seeing a more even distribution because of lower intensities and specific blocks seeing more fluctuation because of higher intensities. In this example, we are only concerned with main lifts of 60% or heavier. Accessory lifts and plyometrics, although important to the training plan, should be tracked separately and will be discussed in a future article.

With repetitions prescribed, exercises can be populated. A basic recommendation is to have each session focus on a singular goal and in this case it will be pulling mechanics in the snatch. The session will start with a technical primer, a movement performed at the 60% intensity zone, in this case no hook, no foot, no contact power snatches will work. Due to the difficulty of this exercise it is best performed in the 2-3 rep range. Given the amount of volume available we can allocate four sets of three reps to this exercise, leaving us two extra reps to allocate elsewhere.

Now to the meat and potatoes of the workout. The exercise used here will depend on the athlete’s individual needs and their proximity to competition. For this article let’s focus on the classic snatch. With 16 reps per exercise, we can break this up into five sets of three reps and an average intensity in the 70-80% zone. After the classic work, a special exercise is prescribed, in this instance a snatch deadlift, for three sets of five reps at 80-90% snatch 1RM. The fourth exercise will be a strength lift emphasizing speed strength and for this particular athlete the back squat seems like a good fit. The focus of the movement should be on lower reps done at high velocity and moderate intensity, say seven sets of two at 70-80%. For our last major exercise, a workout focusing mostly on weakness remediation could be prescribed, in this case a snatch grip RDL to target the low back will be beneficial. With fourteen total repetitions left, two sets of seven at RPE 7-8 would be a great choice.

Example Workout:

- No hook, no foot, no contact power snatch

- 4x3 at 60%.

- Snatch

- 5x3 at 70-80%

- Snatch Deadlift

- 3x5 at 80-90% Snatch 1RM

- Back Squat

- 7x2 at 70-80%

- Snatch Grip RDL

- 2x7 at 80-90% of Snatch 1RM

Go on… stand up

While this article does not hand you ten years of coaching experience, it does teach you the process to coach more effectively over the next ten years. In this case, “better” starts with a process orientation (i.e., planning your training according to both theory and practice). This is juxtaposed with a system-based strategy, focused on trends and templates to improve performance. While knowledge and opportunity is the recipe for success, there’s no forcing anyone to adopt this strategy. If you don’t want to track your training, then don’t, but we here at CoachLogik live and die by the quote from Maya Angelou:

“Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)