The jerk can make or break a champion. After a gritty clean, smashing the jerk will make anyone feel invincible. On the other hand, easy cleans followed by miserable attempts at a jerk will leave a sinking feeling in the stomach of all watching. I have my own experience of this, but it doesn’t end on a positive note.

Weightlifting.ai, the brainchild of CoachLogik founder Max Aita, hosted a training camp in Oakland, California, at the new Max’s Gym—a double-story facility seven minutes from its original home of over a decade. It was November 6th, and the Bay Area weather hovered in the 60s with clear skies. There was plenty of hype in the air as everyone planned one of the final heavy sessions before traveling back home.

I shared a bar with Keith Lyons, a friend and off-the-bench training partner whenever we met up in California or I crashed at his place in Las Vegas. Like any good training partner, we were battling kilo for kilo, with Keith pulling a 120 kg snatch out of nowhere when neither of us dreamed of making anything over 110. Since I snatched 116 kg, I had to take the win in the clean and jerk. After a beautiful lift at 147kg, and what ended up being the winning lift, I walked up to Max and asked what I should take. I told him my best clean was 152, and my best clean and jerk was 151. He prodded me toward 153, and promptly told me to go for it.

The pre-lift visualization, ripping smelling salts until I couldn’t see, the bright lights for filming, and a group of the most incredible people all made for a surreal platform to take a lifetime attempt at a PR clean and jerk – one I hadn’t challenged in 4 years. After walking up to the bar, giving myself some time to slow things down and I pulled on it like I had the previous 10,000 times. The clean popped off of my legs and crashed on my shoulders, but I was able to maintain enough integrity to stand the bar up, shoving my hips at the last second. As I recovered, I finished the clean and took a step forward to readjust and settle, finding a position to initiate the jerk. Once there, I paused, took a deep breath, and drove the life out of the bar… just a touch forward. I couldn’t recover. And that was the last PR clean and jerk attempt I’ve taken and the only one I’ve seriously considered in the last five years.

Seb Ostrowicz of Weightlifting House sums up the feelings devastatingly:

“Damn that’s a shame… you only get to make so many cleans like that.”

You only get so many maximal cleans, only so many clean and jerk PR attempts, only so many made lifts – so don’t waste them because your jerk sucks.

Jerk Primers

This article continues my Technique Primer series, focusing on the jerk, a critical component of weightlifting success. If you aren’t familiar with primers, I would suggest reading that article to grasp what they are, why they are used, and how to incorporate them into a training plan.

Each major movement could in theory be primed – leading to improved technique, better quality work and training adaptations. This series is focused on the snatch, clean, and jerk – very skilled movements requiring mastery with big weights, high speeds of movement, and large ranges of motion.

The jerk, as broken down in The Weightlifter’s Guide to the Clean and Jerk, assumes one of three flavors: power, squat, or split style. For our purposes, we’ll stick to the split jerk, assuming you’re one of the many who adopted the more technical, but forgiving technique.

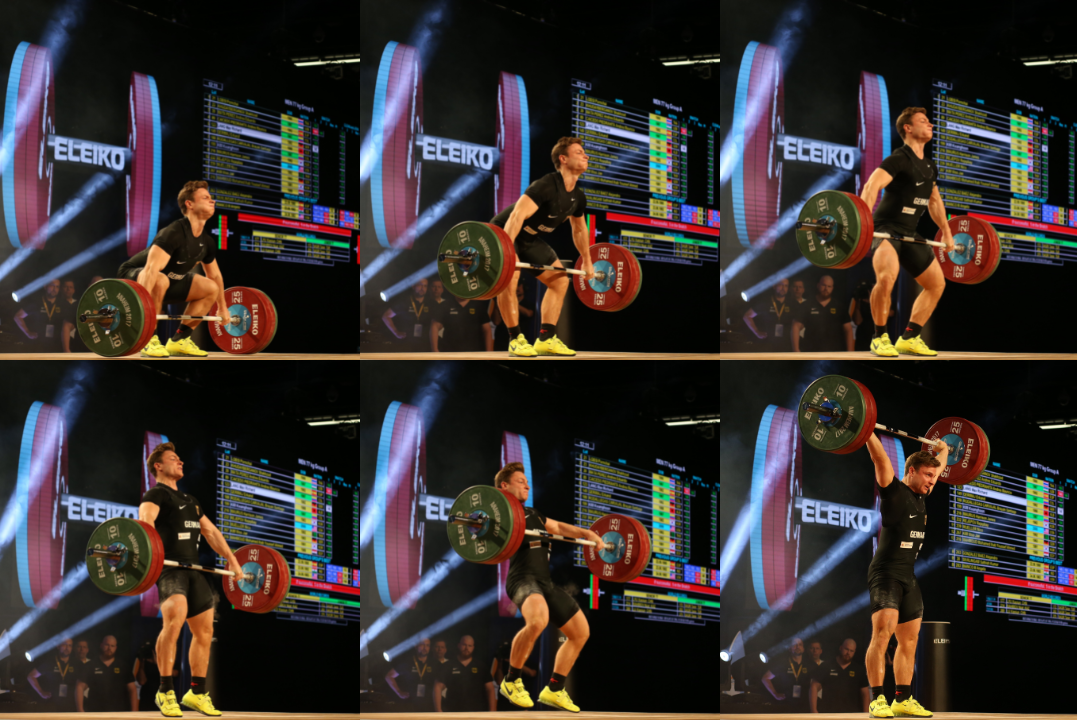

In phases, the jerk requires a dip and drive, split under, fixation overhead, and a balanced recovery of the feet. All of these phases are up for individualization, but maintain the same criteria related to balance, timing, and the ability to express force rapidly. It is helpful to know the phases because it makes identifying where things go wrong easier.

The primers included in this article will address the dip and drive phases and provide you with a platform (pun intended) to build complexity into your training to make big lifts when they count.

The Dip and Drive

Reiterating the point about individual differences in movement, the dip showcases this perfectly, as depth is largely a factor determined by strength, athleticism, and athlete proportions. Some lifters prefer and succeed with a short, snappy dip and others thrive with something akin to a partial squat. Regardless, there are non-negotiable, encapsulated in The Weightlifter’s Guide to the Clean and Jerk:

“… an ever present importance on a balanced and correctly timed dip, with minimal movement of the barbell or front rack position.”

The drive is less subject to preference, seeing athletes extend their ankles, knees, and hips rapidly to accelerate the barbell and create space for the split.

Both phases should be addressed if deficient, either together or separately depending on athlete level and degree of technical needs.

Primers for the Dip

Deficiencies in the dip are often a result of poor balance, timing, or bracing. These issues can be addressed individually or in combination. Here are my favorite primers for the dip and how they can be programmed.

Tempo Dip into Jerk

Tempo dips can be performed in countless ways, but it’s always easier to start simple and increase complexity as needed.

Each variation slows the lifter down to force a more rigid posture, enhance the focus on balance, and prime the correct dip into a jerk to teach the athlete what that efficiency will feel like.

Dips performed Separately (tempo, overload)

When performed separately from the jerk, the dips can be overloaded quite a bit more. This may lead to slightly more fatigue then lower intensity tempo jerks, but earlier on in training cycles, this may drive more adaptations to the targeted movement.

Similar to the jerk variations, these dips are slower and focused on balance + bracing, this time emphasizing load and maintaining a rigid torso.

Primers for the Drive

Errors in the drive are due to incorrect balance and positioning, contributing to a weak extension of the legs. This will comprise barbell trajectory, with it moving forward and in front of the athlete. A weak extension limits bar height, with the athlete unable to split and move under the bar. Primers to enhance this phase of the lift check the box for leg drive and ideal balance, with the athlete improving mechanics, strength, and speed of movement.

Push Press

The push press is a staple exercise in many programs, from weightlifting to strength and conditioning, for good reason. The push press targets the drive phase of the dip and drive, requiring a forceful extension with the legs and follow through with the arms. This exercise can be done as a standalone movement to prime the jerk or part of an “extension-focused” complex to enhance its effect.

Power Jerk

The power jerk is form of jerk adopted as the competition-style technique or as a supportive exercise for the split or squat jerk. This exercise is performed by executing a dip and drive, then punching underneath the bar into a quarter squat position.

Similar to the push press, this exercise can be done as a standalone variation or paired other exercises to create a sequence of technique improving primers.

Jerk Drive

The jerk drive is similar to the jerk dip, but includes a continuation of the movement with the bar leaving the shoulders and driving up a few inches before coming back down into the front rack. This increases the demands on the athlete to maintain a rigid torso and decelerate the barbell as it forcefully travels back onto the lifter.

Slow Motion Jerk

The slow motion jerk is what I would call a tactile exercise, focused almost entirely on bar feel. Slowing the movement down and deliberately executing every aspect of it with intention has the long-term return of achieving mastery. The slow nature of the lift should not be compromised, so added weight should be avoided.

Tall Jerk

The tall jerk as I would perform it sees the lifter dip and drive, rising onto their toes and elevating the bar to about forehead height before snapping under into the receive position. This is another tactile exercise, with a focus on movement quality over the weight on the bar.

Basic Plyometrics

Not a jerk exercise, but low level plyometrics require and enhance proficient use of the stretch shortening cycle and the aforementioned “triple extension”. When placed before jerk variations, the plyos repeatedly expose the athlete to high velocities, jump mechanics, and proficient use of the body to elevate itself, and eventually the barbell.

It Starts with Perfection

Big cleans mean very little without a locked-in jerk. Regardless of your style, the dip and drive is a critical component of success. Errors result from poor balance or extension mechanics, with the athlete sacrificing torso position in the process. Primers that enhance the dip and drive will not only improve your movement, but provide you with the opportunity to jerk like a champion.

The next article in the series will focus on the transition under the barbell, its fixation overhead, and recovery. Because it hurts to miss a big lift under high pressure, but it hurts even more when you didn’t need to miss in the first place.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)