Even if we can’t be the strongest, fastest, or most athletic performers, we can be the most skilled. A scientific article from Hodges & Lohse (2021) explores a framework related to practice design and skill acquisition – the Challenge Point Framework. The authors hypothesize that learning is maximized when the difficulty of the task matches the skill level of the athlete. Coaches can then design training sessions to exploit the exact abilities of each person, with no set/rep/exercise combination being too much or too little, but just right.

From Practice to Perfection

Practicing any skill for years on end doesn’t mean that movement mastery is inevitable. You can do a bad job one thousand times and you’ve only managed to become good at doing something badly.

Perfecting a craft is complicated and reaches beyond the weightroom, court, and playing field. Even so, this belief still persists. Mainstream media (think: Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers) has perpetuated the idea that the amount of time spent deliberately practicing a skill is all that matters in determining mastery (Hambrick et al., 2013).

But the reality is that expert-level performance isn’t as simple as time on the task. Many variables influence movement performance. For athletics particularly, outcomes cannot be chalked up to either “biologically or environmentally deterministic positions” (Davids & Baker, 2007).

A few variables influencing athletic skill include (Davids & Baker, 2007):

- Parents - get athletes into the sport and provides resources (e.g. financial support)

- Coaches - determine the quality of training received

- Culture - determines the probability of a particular sport being played (American Football in, well, America)

- Relative age - determines success within a given group (i.e. the youngest player on a high school team would likely be less successful than the older, all things considered)

While practice is not the only thing determining mastery, it strongly influences the quality of the end result.

Learning to Practice

Learning: Learning is a process designed to improve skills through both initial change and retention from practice. That means that changes intra-session (within a workout) aren’t necessarily indicative of long-term gains – mind blowing, right?

To increase your ability to consistently improve (and do that many practice sessions), challenge performance in a way that provides movement information — both conscious and subconscious. All practice can be good practice, and even the failures which should be expected.

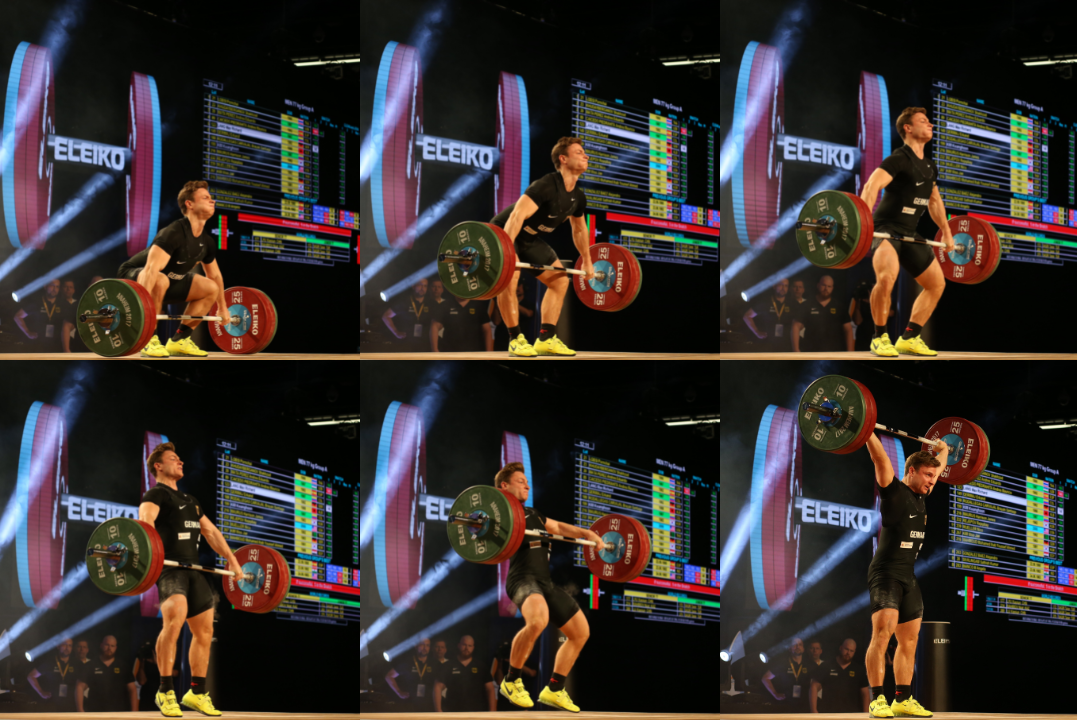

Transfer:Transfer is the degree in which the learned skills impact competitive performance. Learning for the sake of learning can be helpful, but if there is minimal or no transfer to the competitive event, time can be better served elsewhere. For example, a low hang snatch may improve the classic snatch, but something unrelated like a bench press may not have an impact.

Maintenance: When the focus is not on enhanced learning, maintenance – the retention of previously developed abilities – is necessary to maximize performance in a long-term plan. For periods of training where the focus shifts, an allocation of training volume and exercise selection could be geared towards physiological adaptations, less so skill-based improvements. Once these changes happen, (i.e. you build more muscle), the focus could then turn on improving the skill and performance of the classic snatch.

Interplay always occurs between learning, transfer, and maintenance. The training focus will usually determine the extent to which these foci are emphasized. General preparation blocks typically push most of the training volume to technical development, specifically where the athlete struggles most. Competition preparation blocks may lean more heavily towards skill maintenance, focusing less on developing abilities whole cloth. This is not only determined by the competition calendar but also by the athlete.

Practicing to Compete

“Practice is generally considered to be the single most important factor responsible for the permanent improvement in the ability to perform a motor skill.” (Guadagnoli & Lee, 2004)

With all things being equal, practice serves as a strong predictor of how much better someone gets. Although, in the real world practice is prescribed by coaches who are inherently limited in what they know, how they know it, and their ability to execute – what makes sense in theory may not pan out. Athletes come with their own attributes, strengths and weaknesses, that makes the relationship between the athlete, the skill, and the impact on skill acquisition a complex one.

The Red or the Blue Skill

Two types of difficulty — nominal and functional difficulty — can play a large role in skill development and maintenance.

Nominal difficulty refers to the qualities of a task that are held constant, regardless of who is performing it (Guadagnoli & Lee, 2004). An example of this would be the particular exercise chosen and the set/rep/load combination (e.g., No Hook No Feet Snatch – 80% for 4 sets 3 reps). Regardless of who is performing this snatch workout, it retains a high nominal difficulty.

Functional difficulty, in contrast, relates task demand to the athlete’s skill level. For a beginner, this would be an even more challenging task, and less so for an elite weightlifter with plenty of experience performing this movement.

It’s up to the coach to apply the correct amount of challenge to initiate the desired change (maintenance, learning, transfer).

Who Needs What?

For novice athletes, “simple” skills will present enough movement challenge to promote learning (e.g., 20 snatch singles on the minute – 70-80%). For more advanced athletes, the challenge must match the athlete’s abilities, often requiring more difficulty (e.g., a complex including 3-5 different movements to target a single technical change). As the athlete’s skill level advances, challenge must advance, too, ultimately leading toward positive change.

Information relayed from challenging movements should connect the dots. As the athlete’s skill grows, so does the necessary challenge to induce learning. Hence the name Challenge Point Framework. The challenge point is a moving target, lying along the axis of functional task difficulty and available information.

How Does Failure Factor In?

When challenge matches the athlete’s needs, anticipate decreases in performance. Even if told beforehand, this can still be hard to cope with. It is not uncommon for athletes to struggle when implementing new exercises targeting their technical faults or when instructed to make changes. Although we hope for improvement, it can often lead to failure and frustration.

Coaches and athletes should strike an equilibrium between the psychological “tax” and the potential growth in performance. When made aware beforehand, they can face the tax with confidence, instead of potentially feeling blindsided by failure. As with most successful relationships, this hinges on an understanding by both the coach and athlete on the what and how, along with constant communication along the way.

Leave No Stone Unturned

Tough training can lead to improvements in muscle size, muscle strength, or movement skill. If this does not happen, some part of the process should be adjusted to align the two. When squat strength is the goal — but there’s no budge in the movement — then altering intensity, volume, and/or exercise selection will single in on the right form and dose of stress. Infrequently though do we think of technique in a similar light. Currently, if no improvement happens the best strategy coaches can muster is repeating themselves ad infinitum. Instead, if we can reconceptualize this process and appreciate the need for sufficient challenge, the first place we would turn when faced with failure is a recombination of the same variable to make our athletes bigger and stronger.

The Challenge Point Framework aims to explain how challenges in practice can align with the athlete’s skill level to optimize movement development. Challenge can be a moving target, influenced by nominal and functional difficulty, expertly diagnosed and prescribed training recognizes these variables. Expert coaches who know their athletes and their training process are able to best match the athlete with the task. No approach is perfect, but they are all able to be better or worse than the last one, so alway work towards better.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)