Weightlifting is not simple, but it is straightforward. Complexity exists at every level, and this article is an attempt to simplify that complexity. Stemming initially from a conversation with Max, he referenced three questions he implicitly answers during the warm-up of an athlete’s training session. Those answers inform the coaching, maximizing the return on the workout. The job of every coach is to maximize the return from a workout.

Three Questions to Ask While Coaching Weightlifting

Most coaches are great at feeling out the training environment. From asking how the athlete feels to feeding the fire of a Big Friday, much of it can be intuitive and seamlessly learned. But what remains gray —even with coaching experience and expertise — is how to navigate modifying workouts without athlete input.

Each workout should provide the correct training stress to drive a response, but realistically, fluctuations in athlete readiness make this difficult. Paired with the unpredicted response to training, we can’t even be sure the adaptations we want are being accrued without a peek into the athlete’s physiology. The solution is managing key training variables alongside the lifter’s performance potential, maximizing available workout volume and lift intensity.

Question #1: What shape is the athlete in?

This is a question of athlete readiness – creating a platform to manage the session up or down, increasing loading or work. Readiness means the performance potential of the athlete in that exact moment. This is contrasted to preparedness, which is the rolling capability of the athlete rather than a one-off snapshot.

Readiness informs individual workouts, whereas preparedness informs larger training periods. Coaches either intuitively or intentionally pick up on this information.

A large part of the picture of athlete readiness includes bar speed, technical consistency, and efficiency:

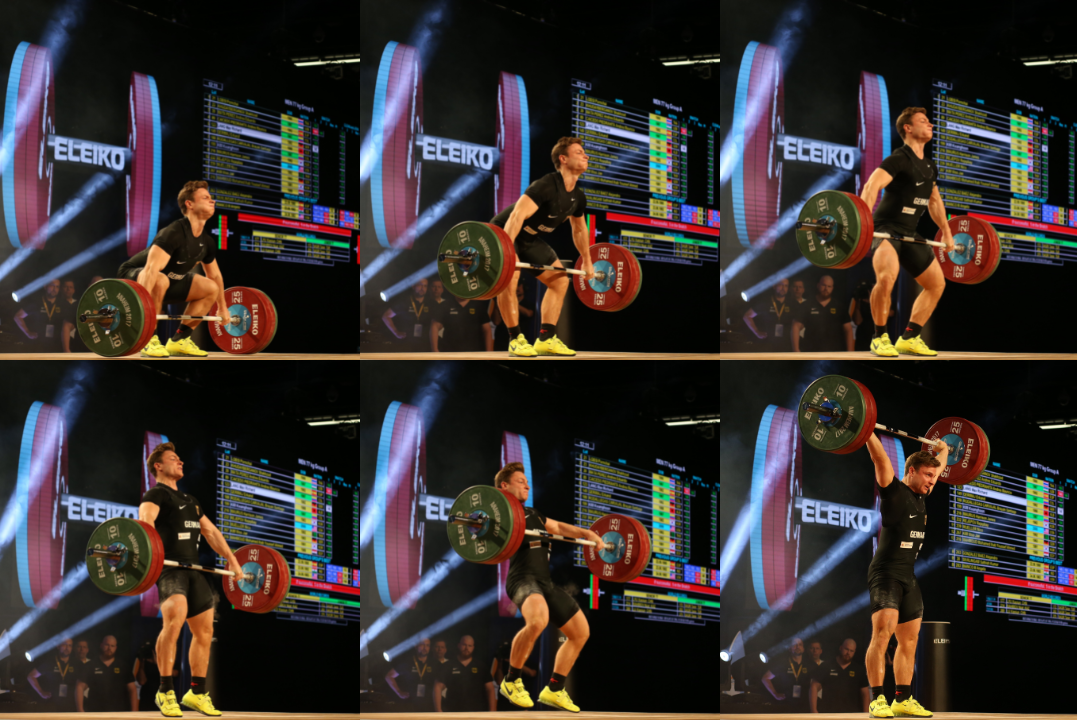

- Bar speed is generally the rate at which the bar moves from the start to the finish of the lift. This is made up of acceleration patterns, with average and peak concentric velocity being the most significant variables within the specified range of motion. Speed of movement is largely dictated by peak force production and its rate of development – which means we can infer a lot about an athlete’s shape by the movement of the bar.

- Technical consistency and efficiency are variables influenced significantly by acute and cumulative fatigue. Intra-session manifests as inconsistent movement, with some lifts being better and some being worse. Session-to-session variance in movement will also increase, with some days being consistent and dialed in, yet others all over the place. A lifter who cannot reproduce efficient movement displays diminished training readiness.

Question #2: How much quality work can we do?

Once you have determined the athlete’s readiness (i.e. bar speed and technical efficiency + consistency) you can manipulate the workout. A maximized training session includes performing as much high-quality work as necessary to drive the correct training response.

Weightlifting is a sport characterized by lifting the heaviest possible weight overhead. This can be done in one or two movements respectively, but maintains the same strength and power demands across both. Effective training overloads the systems responsible for creating movement within specific coordination parameters, driving resources to bolster the force-producing machinery. For that training stress to be properly applied, movements must be efficient and repeatable. Quality work comes when sufficient training is applied to predictable and desired movements.

Coaches should strive to maximize quality work within a session. Now — before this gets taken to the extreme — this isn’t a strategy for doing excessive work but rather takes advantage of the ability to add sets or load when possible. When developing technique, muscular size, strength, or other physical qualities, the more, the better. A heuristic I use from a technical perspective is how the movement changes across sets and within the workout. If the movement improves, add another set to dial in the adjustment. Further imprinting quality movement is critical in this sport. Don’t miss an opportunity to lift more efficiently at progressively heavier weights.

For hypertrophy or work capacity purposes, adding volume (within a bandwidth), can create a stronger signal for change. Knowing exactly the amount of training to do to get bigger is a nearly impossible task, but gauging readiness and determining when and how to add work can close the gap.

Question #3: Can we go heavier?

One point reliably brought up on the Philosophical Weightlifting podcast episodes with Max is evidence indicating the strong correlation between the number of 90% lifts in a program and improvements in results. Generally, the heavier the training, the better. This does not support maxing out every session or bypassing lighter phases of training for only high-intensity blocks. Instead, this indicates that the more intense training can be on average, the more you can anticipate performance improvements.

With that in mind, how heavy should you go within a session? Using the established program as a guardrail, making changes to the prescribed intensity can more precisely match the difficulty of the session with the athlete’s readiness, along with what’s most likely to improve their abilities. This isn’t only limited to the competition lifts and their variants, but it is where this tactic is mostly used. Developing unnecessary fatigue from pushing all movements, all of the time can be a fool’s errand. Good coaching is picking the right moments to change the plan, to exploit unpredictable variations in physiology.

Knowing exactly how the athlete is adapting to training is not as straightforward or as simple as we would like. Performance can be messy, and the ability to read it correctly falls on connecting different pieces of data. One surefire way to know if you are on track is in the programming itself. If you are consistently increasing the weight on the bar each session above what is predicted, you’re in a good spot. This strategy for coaching is both a symptom and a result of great programming and coaching.

Good Coaching is Active Coaching

Maximizing your athlete’s results requires good coaching. Walk the floor, watch the training session intently, and make decisions that drive or support the desired training responses. Good coaching is being active within a session, deciding what needs to happen and when. Although athletes are the only ones privy to their internal sensations (e.g., soreness, perceived fatigue, energy levels), coaches can tease out quite a bit of information, especially information relevant to performance or performance potential.

Understanding the role of athlete readiness, training volume, and training intensity in developing bigger snatches and clean and jerks is critical. Using the above questions to guide intra-session coaching can level up anyone’s game. But like anything, they can be answered incorrectly. Time and experience can refine your ability to answer simple questions like adding sets or putting more weight on the bar.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)